BREAKING CODES

BREAKING CODES was a weekend-long event that highlighted three artists, Nick Briz, NIA JUNE, and Amina Ross, emerging moving image makers who build radical, expansive, and wholly new definitions of cinematic form. In addition to four free in-person events hosted at the SNF Parkway Theatre from December 9-11, an online exhibition of selected works from the artists was presented alongside an interview conducted by a colleague from December 12, 20222 through January 2, 2023.

MEET THE ARTISTS

NIA JUNE is a Baltimore native, author, filmmaker, performer, arts educator, and dancer. Her short film work combines original poetry, portraiture, movement, and music collaborations to document and celebrate the Black diaspora of Baltimore and beyond. JUNE’s debut film, A Black Girl’s Country, appeared in national and international film festivals and was acquired by The Baltimore Museum of Art as a part of their permanent collection in 2021. JUNE’s writing has been published in Obsidian: Literature and Arts in the African Diaspora, Lullwater Review, and FIYAH Lit Mag. JUNE graduated from Towson University, where she was awarded the Presidential Scholarship from SWI for ‘Excellence in Poetry.’ She was recognized by Baltimore Magazine as Best Poet of Baltimore 2020.

Nick Briz is an internationally recognized new-media artist, educator and organizer. His work investigates the promises and perils of living in an increasingly digital and networked world. He is an active participant in various online communities and conversations including glitch art, net art, remix culture, digital literacy, hacktivism and digital rights. He’s co-founder of netizen.org a nonprofit focused on digital literacy and digital culture, he’s Associate Professor Adjunct at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Lecturer at the University of Chicago, and a freelance Creative Technologist.

Amina Ross is an artist, educator, and lifelong learner. Ross makes videos, sculptures, sounds, and situations that consider feeling, embodied knowledge, and intimacy as survival technologies for black, queer, trans, and feminine-spectrum people. Their work questions how systems of power condition reality and how communities facing oppression navigate, resist, reimagine, and refigure these systems to thrive in safety. Ross worked as an educator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, was a lecturer at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a critic at Rhode Island School of Design. They received a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA from the Yale School of Art. They have recently exhibited work at Sentiment (Zurich, CH), Wave Hill (Bronx, NY), The Luminary (St. Louis, MO), Iceberg Projects (Chicago, IL), M23 (New York, NY), Springsteen Gallery (Baltimore, MD), and Centro De Cultura Digital (Mexico City, MX) among other venues. Ross was a recent artist-in-residence at Skowhegan School of Sculpture and Painting (Madison, ME), Wave Hill (Bronx, NY), Abrons Art Center (New York, NY), and Harvestworks (New York, NY).

NIA JUNE

A Black Girl’s Country

A short film and visual poem celebrating black women. After Ntozake Shange.

Keep What You Sow: Homegrown Industries of Baltimore

A short film about Black, Baltimore-natives leading industries in their hometown.

The Unveiling of God / a love letter to my forefathers

A visual poem and short film directed by Nia June and APoetNamedNate and shot by Kirby Griffin.

About the Interviewer

Christy LeMaster is the Artistic Director of the SNF Parkway Theatre and the Maryland Film Festival. Previously she lived in Chicago for 15 years where she worked as a programmer, educator, and producer interested in collectivity, platform, and collaborative processes. She founded Chicago’s cooperatively-helmed microcinema The Nightingale and co-programmed itinerant experimental doc series Run of Life at spaces around the city, including experimental music venue Constellation. From 2017-19, she worked as Assistant Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, organizing programs and exhibitions for the Commons, the museum’s site for art and civic engagement. She taught media theory at Columbia College Chicago, has been a movie critic on WBEZ, and an editor of CINE-FILE.info. Her writing has been published by INCITE Journal of Experimental Media, Brooklyn Rail, and Green Lantern Press.

Interview with NIA JUNE

Christy LeMaster: Hello NIA, First off, thank you for this interview! It is a delight to have some space to think about your work with you in this format. Written words for the writer! But that is only partially right, because you are truly a multi-disciplinary artist working with text, filmmaking and dance. Will you share how you developed your current practice? Does the poetry lead the way into crafting images? What lets you know when an idea is about to become a working project?

NIA JUNE: Dance is the mother of my work. In its most embryonic form, each film is the emotion I am left with after moving or watching a dance performance. The Unveiling of God / a love letter to my forefathers, for example, revealed itself to me after I saw Dance Theatre of Harlem perform “This Bitter Earth” at Morgan State University in 2019. Choreographed by Christoper Wheeldon, this emotional pas de deaux made me wonder about the relationship between Black men and women— which led me to think about my own relationship with Black men. I went home and immediately started the film treatment.

Because dance plays such a pivotal role in my filmmaking process, sound is also a major influence. As a dancer and spoken word artist who relies heavily on rhyme and rhythm, it is important that each film work uses music and images collaboratively— allowing both forms to be in conversation with one another. As a multidisciplinary artist, I also understand that everyone answers to a different art form. While music may move one viewer, another may be captivated by words or movement. My ultimate goal is to make the work multilingual in its emotive and artistic elements.

Christy LeMaster: I admire that nonfiction quality of your work. The way you invoke portraiture and tableau compelling and beautiful. There is a sense of a real connection between the camera and the people in front of the camera in the works. Can you share a little about how you choose people to work with and how you build connection onscreen and off?

NIA JUNE: We take a documentary style approach to casting. Majority of our subjects are people we know or have encountered. Rather than hosting casting calls and auditions, we seek out individuals and families whose stories align with our vision. This allows us to uplift the real faces that make up our community, all the while manifesting a mirror for our people and assembling a collage of our own memories.

The entrepreneurs featured in Keep What You Sow: Homegrown Industries of Baltimore are folk who’ve served the Baltimore community for years. For my co-creator and cinematographer, Kirby Griffin, the Carey Hardware moniker was a constant in the scenes of his childhood and now, his adult life. My very first featured poetry performance was during an event hosted at Illicit Rag Vintage and I’ve been shopping there since. But we didn’t just highlight these four businesses because they’re our friends, we highlighted them because their work is important, it serves Black people, and they deserve to be seen just as much as your local Target or cherished chain restaurant.

The men in The Unveiling of God / a love letter to my forefathers are representations of my father, grandfathers, and uncles— men who were born and raised in Baltimore and spent their lives trying to master what it means to be Black and male. In addition, many Black stories don’t make it to the big screen unless they feature a violent death, racism, poverty, hyper-sexuality, crime, or an immense struggle. While these stories can be true and are valuable, for many of us the truth is also as simple as three Black boys spending the day riding their bikes or three generations of women sitting in the living room talking about plans for tomorrow. Sometimes, the truth is as commonplace as roaming your neighborhood looking for something to do. All in all, the Black community of Baltimore is a multilayered one and the best way to capture its truth is through the faces that define it.

Christy LeMaster: Your videos resonate with the experience of observing and moving through Baltimore. You capture an authentic sense of our city in the way you choose sites and locations. What inspires you to make work here?

NIA JUNE: Most of the images we create are derived from memory. And most of our memories take place here. Kirby, APoetNamedNate, and I grew up in Baltimore and carry its stories inside of us. We love Baltimore and we want to capture its beauty, its people, its color, its traditions. Most of all, the people inspire me. In A Black Girl’s Country we featured young dancers of Baltimore Dance Tech, a pillar in the Baltimore dance community. The dance school is run by Stephanie Powell and is my alma mater—from 2000 to 2013 I spent Saturday mornings and weekday evenings there. BDT is located inside an old church on Route 40, on the cusp of Baltimore County and City. Some of Baltimore’s most successful dancers trained under Ms. Stephanie in that church. Being able to capture this legendary studio was a full circle moment for me and shed light on the importance of space in our lives and in our work. We also highlight some of Baltimore’s grimiest backdrops. The juxtaposition of beautiful people up against dilapidated row homes or overgrown patches of grass speaks to the resilient and multilayered culture that is Baltimore.

Christy LeMaster: What are you working on now? May we look forward to new NIA JUNE works in the new year?

NIA JUNE: Right now, my team and I are exploring new ways to expand and evolve the style we’ve developed while still maintaining our mission to tell stories about Black people in Baltimore in an honest and original way. We are currently looking for funding for a new project! Please feel free to reach out if you are interested in supporting us.

NICK BRIZ

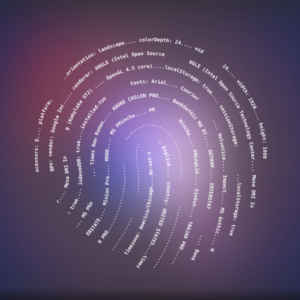

How They Watch

A hypermedia essay on how online tracking works, why it works the way it does and what’s at stake.

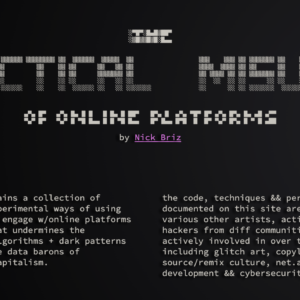

Tactical Misuse

a collection of codes, scripts + techniques for tactically misusing online platforms

Framed Picture Gallery

FramedPicture.Gallery is a virtual space about virtual spaces. Specifically, it’s about seeing the way virtual spaces dictate what we see.

About the Interviewer

Shawné Michaelain Holloway is a Chicago-based new media artist and poet. Known for her noisy experimental electronic and performance practice, HOLLOWAY shapes the rhetorics of technology and sexuality into tools for exposing structures of power. She has spoken and exhibited work internationally since 2012 in spaces like Performance Space New York, The New Museum, The Kitchen, The Time-Based Art Festival at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, Institute of Contemporary Arts (London), The Knockdown Center, and the NRW-Forum Düsseldorf. SHAWNÉ is currently Assistant Professor of Video/New Media in the Kinetic Imaging department at Virginia Commonwealth University and is the Digital Developer and Technology Manager with Black Lunch Table’s archives team. She was selected by the Museum of Contemporary Art’s 2022-23 New Works Initiative as the current Chicago Performance Commission recipient. In addition to her fine arts practice she is a dedicated open source software advocate and a powerlifter.

Interview Assistant

ChatGPT is a prototype artificial intelligence chatbot developed by OpenAI which specializes in dialogue. The chatbot is a large language model fine-tuned with both supervised and reinforcement learning techniques. It is based on OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 model, an improved version of GPT-3.

Interview:

ON NICK BRIZ : NICK BRIZ X SHAWNÉ MICHAELAIN HOLLOWAY X CHATGPT

“We need to carve a path into the future where machine learning is for us, not against us.The thing I’m most excited about is the thing I’m most scared about. I see so much potential.“

On Thursday, December 8th, artists Nick Briz and SHAWNÉ MICHAELAIN HOLLOWAY had a general conversation about Nick’s research and practice. A central theme of their exchange was about the way the tech industry nonconsensually harvests large amounts of personal data to train artificial intelligence lgorithms. This conversation was exactly 26 minutes long.

They asked an AI (the kind we’re talking about that learns from our data) to both summarize and speculate about elements of their chat. What follows is not the conversation itself, but instead an entirely AI generated bio of Nick Briz, his practice, and what is to come from his research. It accurately stated the following information:

“Nick Briz is an internet artist, educator, and organizer. He creates work about the technology that has come to define the current era. Briz believes that the internet is an era-defining technology, and enjoys making art that helps people better understand and see the moment in time that they are living in. Briz’s art is often created using technology itself, and comes out of researching and experimenting with the technology. In this process, Briz learns about the history, design, and potential of the technology.

Briz’s work often tackles big, abstract ideas such as surveillance capitalism and privacy. He believes that his art can make these complex issues accessible and understandable to people. Briz also believes that art can be a powerful tool for creating change, and that it can help people see things that they might not otherwise see. When asked about the role of artists in the current moment, Briz said that artists can help people gain perspective and see things differently, and that this is an important part of creating change.

His artwork often takes a technological form, such as data-driven pieces or algorithmic projects. If seen in person, his artwork might include interactive installations or digital displays. It is likely to explore complex and abstract ideas related to technology and its impact on society.”

HOLLOWAY and Briz then asked the AI to share its opinions on their conversation and on Nick’s practice itself. It offered the following critique:

“Nick Briz seems to have a good relationship with the interviewer, and they seem to be on the same page about the importance of technology and its potential impact on society. However, it remains to be seen whether or not art can actually create the kind of change that Nick is hoping for. While art has the ability to inspire and challenge people’s perspectives, it may not be enough on its own to effect the kind of systemic changes that Nick is advocating for. It will likely require a combination of efforts from various organizations and individuals to create the kind of impact that Nick is hoping for.”

To learn more about Nick Briz, from Nick Briz himself, visit his website at nickbriz.com, his Youtube page at https://youtube.com/@NickBriz, or the project he leads called https://netnet.studio!

AMINA ROSS

A Bridge, [A Black,] A Barrel, A Back, 2015, 6:23

Screen recorded powerpoint video component of the “A Bridge, [A Black,] A Barrel, A Back” series which consists of video, objects and costumes.

Emotional Weather(1), 2020, 6:19

Audio produced in collaboration with musician Isaac Pross.

“Emotional Weather(1)” is an exercise in emotional range designed, facilitated and recorded by Amina Ross. This iteration is performed by actor Yel Rennals. This video and sound piece are a part of a larger on-going body of work entitled “Sonic Rupture: songs for(e) the swarm” by Amina Ross and collaborators.

Specular Cry, 2020, 2:28

Short video visualization, with audio co-produced by Charles Rice.

About the Interviewer

Bao Nguyen (they/them) is a performance artist, experimental vocalist and curator born in Vietnam and based in Baltimore. They are pursuing their BFA in Interactive Art at Maryland Institute College of Art. Bao recently completed their residency at Yale Norfolk Summer School of Art. They have exhibited in the U.S and abroad, including shows at Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and Ewha Woman University, Korea. In 2022, they were awarded the Judson-Morrissey Excellence in New Media Award from the New Media Caucus. Through performance, sound, video and interactive media, Bao’s practice examines oral traditions to reconsider the history of Vietnamese nation-building and devise new ways of connecting to a landscape, to ourselves and to each other.

Interview:

ON THE WORK OF AMINA ROSS, INTERVIEWED BY BAO NGUYEN

(Note: this interview has been transcribed from a video recording and has been edited for a written format.)

Bao Nguyen: I’m curious about your process for scripting and producing video work. Could you show me more about how ideas, words, language, and visuals have been integrated to tell narrative fragments in your work?

Amina Ross: The opening of ‘Man’s Country’ has a line that talks about being in a basement of accumulated objects. I’ve been thinking a lot about the word ‘accumulating’ and what it means to collect, gather, and forage. That line came from my own experience reckoning with objects while moving back into my grandmother’s home. I’m also thinking about my grandmother’s relationship to objects and how her house, which she’s lived in for over 50 years, is a space of accumulation. So, to answer the question, the idea of accumulating or gathering is also how I think about language. As I move through different spaces – the train station, the sidewalk in New York – there’s an abundance of advertisements and I feel like my consciousness is like a sponge, soaking up language from billboards, bits of conversation from people on the train, taglines on soap, voicemails from friends, and texts I read. There’s this drawing in of language from the outside world, and that’s where a lot of my text comes from. It’s like what is around me and how it affects me.

One of my processes is to put language to my experiences and feelings in the world. I spend time understanding my inner and outer worlds and how they’re connected. I often integrate dream journals, texts from diaries, and my own poetic work, along with bits of found and appropriated language. There’s this interplay of words between the inner and outer world. In terms of dialogue and monologues in my more recent work, like ‘Man’s Country’ or ‘A Bridge, [A Black,] A Barrel, A Back’ the dialogue sometimes comes to me in a way that’s similar to how Toni Morrison described her characters appearing to her and telling her their stories. Mine aren’t that vivid, but I receive bits of language through moments of stillness, meditation, or free writing, and they don’t feel like they’re coming from me, but from somewhere else. I think there’s something about where these texts from the outer world, inner world, and another world come together in my consciousness and art practice, holding space for multiple realities to exist together. I think this relates to navigating the world in a body that exists at the intersections of various forms of power. I’m constantly holding multiple realities as I move through spaces. So, how does the work become a container for these realities? I think that there are many spaces that we navigate through. One that I site often is environmental professionalization, or the desire for professionalization. They ask us to make ourselves tidy, neat, and often singular, not holding space for our full selves to be present because it’s seen as improper or inappropriate, and so I’m oftentimes interested in how we can hold space for the depth and breadth of being alive on this planet. In a big way, that’s through text.

Bao Nguyen: Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to holding on to all of your packages, materials, and objects, and by that, I mean all the emotional experiences that you have, so that you’re not becoming a ghost of yourself. It’s like your mind is somewhere else yet your body is here, and you are not whole. What I noticed in all these videos is that they allow for these different realities to exist together and it doesn’t have to be fully understood. Maybe that’s an observation, but maybe my question is, why video? Why is it a compact format for trying to hold on to so many things?

Amina Ross: That’s a great question, and a question I ask myself often, because a lot of the things you would attribute to video, to the history of cinema, to mass media shapes what the media industry looks like today. The industry is comprised of Hollywood cinema, but also at this point sponsored YouTube content. I have a lot of qualms with the media industry and the ways financially driven makers and supporters of media think about the people who are consuming media. I believe that we are often treated as passive recipients of information and ideology of beliefs, rather than being encouraged to ask questions and think for ourselves. For example, how many of us have had our fantasies about love shaped by Disney movies? These movies often tell us what things should be and what they are, and this can be aspirational in a way that reinforces dominant power structures, like the desire to be rich, white, and heterosexual.

I find the tools of this industry very seductive, like video editing and the power of sound and storytelling. But I also think that these tools can be used in expansive and wonderful ways, and I think we see that too, like when you see a movie that shows a version of reality that has never been imaged before, it allows us to stretch our capacity around what can be. I want to resist the temptation to create coherent and cohesive narratives that may do the work of fragmenting our reality further. So, in order to break that down a little bit: in order to create a relatable story, we may want to include a relatable character, so what does a relatable character look like? Maybe we can’t have a queer, Black, polyamorous character because it is considered too niche. I think that in order to make a story that makes sense, is palatable, or sellable, we often make a series of compromises that skew towards whoever is most in power. So, I’m giving up on the project of neat storytelling altogether and I’m instead interested in how to maintain the viewer’s attention.

I have found that when I show my videos to a wide array of audiences, they might not be for everybody, but almost anyone can have a connection to them, and do. At a recent show at Wave Hill, I shared ‘I Am Under’, I had a man who was in his sixties and a retired schoolteacher tell me that the work was deeply resonant and one of the most impactful things he had seen. He felt so connected to the work that he was coming back the next day. And I was like, that’s cool, I wouldn’t have expected that.

I find it exciting to play with the tools of cinema, like rhythm, pacing, and elements that connect to our bodies and pull on people, but not towards the means of telling a neat story. Because I’m playing with these tools, there is potential for a wide range of people to connect to the strange stories I’m telling, and I find that exciting. I think one of the pitfalls of experimental video is that it can be alienating or inaccessible. I don’t want to alienate people with my work, I want to connect with them, but I’m trying to find new ways to create connections without synthesizing ideas or streamlining a story. I’m trying to create new pathways for people to connect and find meaning in the work.

Bao Nguyen: I think this is really important, and before I ask my next question maybe we can talk a little more about this. I feel like for a story to be told effectively, breaking out of the traditional format of the medium might be necessary. There’s something really unnerving in some of the videos, like a spookiness or seductive quality that sucks the viewer in and makes them want to know more, while subverting their expectations about what will happen next. I find that really impactful. For example, one of the videos that does this really well is ‘Emotional Weather’. It starts by presenting sadness, and then slowly the beats start to bring you in, and then there is this explosion of emotion when there is no longer a way out for the viewer. I’m already hooked in, the ride has started, and we have to go on the ride. This forces the viewer to experience emotion in a way they haven’t before. So maybe the question is, how do you use the seduction of media in your work?

Amina Ross: I feel like what you said specifically relates to the idea of lovingly pushing people into a place they may not be drawn to go. This is similar to how I think about teaching and being an educator and facilitator, which is really important to me. I would like to develop more language around how I view my artwork through the lens of facilitation that I have learned through my work with various organizations, like TCA, the teen agency at the at the Museum of Contemporary Art, and also Cooperation for Liberation, and various queer arts collectives like F4F and Beauty Breaks. There is an art form to holding space with a group that requires creating a respectful and safe environment. However, the conversation around safe spaces has become convoluted and complex. There are certain things we can do to ensure that when people enter our space, they will be safer than they would be entering into a conversation on the sidewalk. These include basic levels of care and respect for people’s identities, time, and bodies. While these things are complex, there are tools of facilitation that allow us to hold space for a variety of moments, both difficult and joyous, beautiful and ugly. The real art of skillful facilitation involves immense creativity and responsiveness to complex dynamics in a group, especially in spaces like restorative justice conversations. Those dynamics are so deeply impressive to me and it feels like an art form that unfortunately not many people have witnessed. The art form of facilitation is not through witnessing, it is through participation. I’m really informed by that idea of what it is to participate in a thing and I’m constantly striving (inspired by the art forms of facilitation in education and pedagogy) to have my work be as dynamic as the spaces that I greatly admire and have learned from.

I think that you know it’s unfortunate that I often find within “fine art spaces” that work that is considered “educational” is oftentimes pinned as being reductive, didactic, and easy to digest, however the most talented educators I know are able to hold such complexity and are so dynamic in their thinking. The types of educational models that I’m inspired by are exactly what I hope my work will be: dynamic; able to hold complexity; engaged in constant inquiry; engaged in iteration; non-hierarchical; invested in a sense of just-ness; invested in the ongoing messiness of utopian projects—striving for a better elsewhere. These are not simple things.

I find that in “fine art” contexts education, or what it is to be an educator, invested in this messy work has somehow been made a very sterile or tidy thing, although sometimes the opposite. This loops back to media because media is probably one of our biggest contemporary teachers. How many of us sat in front of the TV while our parents were at work? it was one of my first teachers, I learned a lot of stuff on the TV (that I wasn’t actually allowed to watch). The goal of television, subliminally or overtly, is to teach us something, many times to teach us what to buy and who to value. I am really interested in viewing my engagement with media through a pedagogical lens, or through the lens of teaching, to put it simply.

Bao Nguyen: One thing I noticed in your video works is that you able to hold the audience attention, and then there’s also your attention, and your way of looking through reality to this metaphor of material. Through your own lens, you look through the body, but there is also the lens of the viewer — through your camera you have implied the viewer’s body. The body becomes this sensing agent, navigating the complex reality of this video. I wonder, how do you think through or empower the body in your videos, while also empowering the bodies of your viewers?

Amina Ross: I often times use my own body in the process of making my work even if that is not visible in whatever the final outcome is. For example, in ‘Man’s Country’, I didn’t have a floor plan of the space so I used found footage and found images to recreate the space and worked off of those dimensions to imagine where things would be in relation to the dimensions of my body. I made tape lines on the floor that were the size of the room and based the space off of how I could move in those dimensions. So, I was using my body to measure space. In the video “I Am Under” I was using my body to imagine cutting through the landscape or cutting through barriers—cutting through moments of containment or stagnant energy and repeating these gestures through dance as a way to stir the air around me, and that was a pathway into the writing. I think about the body and my relationship to experimental dance in movement as another way of thinking. We oftentimes place thinking as soley with the brain, placing an emphasis on intellectual thought and reason. In using my body, I’m thinking about opening up space with a gesture and what can arise from that.

Often times when my body is shown through video, it’s me trying something out. I am often trying to learn something in making the work. When I’m thinking about the bodies of others watching the work, I’m often thinking about the work spatially using all the senses. So, I think about how close the person will be to the screen, how close will the audio of the voice will sound to them, how is the relationship different if I’m whispering? How might the vibrations of rhythm make someone want to move their knee? Will it increase their heart rate? I think about what the physical experience of this work is.

I feel very influenced by having a basic meditation practice and body work practice. I do all types of body work, meaning moving my body in different ways to learn things, like stretching, dancing, and yoga. For example, with meditation I really love the idea of just feeling a minute pass. Really sitting with a minute with nothing else playing. Then, while I’m making a video, I think, if I add this sound or image how does that minute pass differently? I watch my videos quite literally hundreds of times, and I enter a space of trying to understand what it fully feels like for me to sit with this many minutes, and how did this video transform these minutes.

While I’m sitting for meditation, honestly, I’m only able to sit for ten minutes max, I had a longer practice before the pandemic but lately I’m at ten minutes on most days. Sometimes it’s three minutes because of my attention span right now. Because I’m used to sitting with minutes on their own, I am very aware of how time is transformed when a video enters into the sphere. I notice the changes in five minutes in my own mental space versus five minutes with a video. My meditation practice has allowed me to become more familiar and closer to time as its own material. Just like through being a master printmaker you get the feel of a certain paper or a certain ink, for me meditation has been what it is to get a feel of time as a material. When I am in the space of receiving the work that I’ve just made, I’m really seeing how the work lands in my body with the way that that’s transformed time.

Bao Nguyen: One video in particular that really hooks me conceptually and emotionally is ‘Emotional Weather’. Could you describe a little more about this work in relation to ‘Sonic Rupture: songs for(e) the swarm’ which is the larger body of work that this piece is a part of? I think this video sums up so many of your interests in a really packed format.

Amina Ross: There are a few things I would say about this video, I would say that the collaborations which are part of that video in particular are especially poignant and powerful in the ways that the final videos realized. Yel Rennals (the actor in the video) is a longtime friend and a deeply skilled actor in terms of her commitment to pushing herself, trying new things, and being curious about her own interworld and how that can be made manifest to her character. Isaac Pross (who’s the musician who I worked with) recorded this track together in person and then worked on it remotely throughout COVID. Isaac’s music has a really strong sensibility, and he has so much technical proficiency with the tools that he uses. More than that, we were able to share a similar headspace in terms of the way that I would describe I describe sound as place. So as an example, I’d say, I want to start out ethereal in the clouds on a pink sunrise, and as the storm rolls in we descend into a cave that unfurls onto a street. That’s just an example, but that’s how I would describe music, and he knew exactly what I was talking about. There was a way that we would speak through sound spatially that was truly special and is not possible with all musicians.

Those two collaborations and those individuals’ connections to their own mediums, and how we were able to connect together around the vision was really crucial to the depth that this work is able to go to. I’m interested in how being fluent in an in a set of technical skill is to be like fluent in a language, and when we have greater language fluency, it allows for the level of “conversation” to be deeper.

Before approaching Yel and Isaac, I had drafted an exercise, the ‘Emotional Weather’ exercise, which is a prompt where I work with actors to shift from the state of hysterical laughter to hysterical crying without drawing from imagination, while staying as present as possible in the space. I pulled on this language, ‘hysterical’ because it’s often been an engendered way to dismiss the emotional and affective suffering of a feminine people and Black people, specifically to hospitalize women. Hysteria was a legitimate way to have women hospitalized in inhumane facilities. I am interested in this idea of a display of emotion or comportment that is considered so out of the norms of the environment that it is disruptive and punishable. So, that was a way to try and attempt to enter into states of hysteria. I was only interested in working with actors because I think that trying to do this with people who aren’t trained could be emotionally irresponsible. It’s important in carrying this out to work with people who are very skilled, who are used to traversing this range. I wanted to traverse this intensity with people who know how to care for themselves through it. I’m not interested in pushing people outside of the realm of their physical and emotional safety.

The exercise is almost is designed to fail, that was not my intention, but it works against any type of pretend emotion, and so it is deeply challenging. Yel actually said that it was a very hard exercise. So, it naturally produced “failure” and I actually enjoyed the failure of it more so than what a smooth transition between intense states of being would look like because we’re not machines—to actually enter those spaces is deeply challenging. So, what is it for us to then take the few minutes of the video to sit with the challenge to perform? I think that like many of us are confronted with the challenge to perform various states of being on a daily basis, like the challenge to perform personhood in the context of a of a country that like only granted Black people personhood not too long ago, and in many states this year alone was up for debate.

There’s also the challenge to perform professionalization, the challenge to perform gender, the failure to perform worker. There are daily failures to perform which have very real implications for many people.

I’m thinking about right now the mayor of New York, Eric Adams is implementing programs to institutionalize people who are visibly mentally ill in New York. If our mental illness takes us to a space of a failure to perform neuronormativity, then you are now able to be institutionalized against your consent. We are seeing the consequences of failing to perform emotional and visible comportment in the world. This is scary and has gotten worse even since the time that I made this work. I made this work on March 16th, 2020, right before the borders closed between states on the East Coast due to COVID.

Bao Nguyen: I think this all related, because you are really speaking to the core, and the heart of the work. Thank you so much for the conversation.

Amina Ross: Thank you! It feels good for me to end with one more comment on the work: however abstracted or experimental my videos may be, they are, for me, how I’m interacting with the very real systems of power and control that I’m interacting with every day. I don’t attempt to abstract them, I attempt to reckon with them most directly, with the tools that I have at hand.

PAST EVENTS

Friday, December 9 at 7:30 pm

NIA JUNE

For the first program of the weekend, Baltimore artist NIA JUNE will present an evening of video works alongside a conversation with her collaborators Kirby Griffin and APoetNamedNate. A poet and performer, NIA JUNE creates moving image works that incorporate spoken language and music to lovingly document the people around her. Using constructed and found environments as backdrops, NIA JUNE invokes tableau and employs choreography to create an evocative connection between viewer and subject, leaving an impression of closeness between those in front of and behind the camera in her works.

Saturday, December 10 at 4 pm

Nick Briz

Chicago artist and technologist Nick Briz joins the SNF Parkway Theatre from Chicago to present a performative lecture and screening on a topic synonymous with our digital age: online surveillance. Often discussed as solely an issue of digital privacy, Briz illustrates how deep the rabbit hole truly goes through his digital artworks, showing the audience how tech companies might know much more about you than you might realize. Although Briz’s works are critical of many contemporary tech and internet-based companies and their practices, he doesn’t cross the line into digital nihilism—instead he offers practical solutions for caring for oneself online, and posits how our hyper-connected overlords might better use their tools to help mankind, as opposed to doing what capitalists do best: making money off of their users. Through artful visualizations, videos, and informed discussion, Briz helps his viewers to understand and contend with the current online surveillance state.

Saturday, December 10 at 7 pm

Amina Ross

The SNF Parkway Theatre is proud to present eight short video works by artist Amina Ross as part of Breaking Codes 2022. Amina’s work comes from a place of acute sensitivity. Sensitivity to images, sounds, feelings, histories, and fellow artists and collaborators. Ross’s work encompasses oceans of emotional and spiritual connections, all while working in what can otherwise be considered cold and unfeeling digital space. Combining new media and digital video tactics, Ross confidently weaves stories, songs, poems, and dreamscapes into moving experiential artworks that posit new modes of relating to oppressive power structures big and small.

Sunday, December 11 at 2 pm

Tactical Misuse Workshop led by Nick Briz

Join new media artist and technologist Nick Briz for a workshop discussing “tactical mis-use” of internet applications, social media websites, and more.

“We don’t just use these online platforms, we live online. these are not just tools, this is our environment, && “as human discourse adapts to its new home, everything we do and think as human beings will be and is being shaped by new values” (Virginia Heffernan). these new norms + values are increasingly being influenced by the logic of surveillance capitalism, && when we use these online platforms we, consciously or not, perpetuate these new values. but there are ways of using (or misusing) these online platforms in a manner that undermines the exploitative algorithms + dark patterns designed by the data barons of surveillance capitalism: the practice of tactical misuse, here’s how.”

— Nick Briz

Breaking Codes is made possible by a generous contribution from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.